But Trailing Clouds of Glory Do We Come

an essay by Jonathan M. Clark, independent critic

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:

The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star,

Hath had elsewhere its setting,

And cometh from afar:

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come…

— William Wordswoth, Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.

Daphnae Koop’s abstract pieces are both heavy and elegant, muscular and mysterious. Their physicality projects such presence, yet their details point to so much ethereal intricacy. But Trailing Clouds of Glory Do We Come trains that dynamic visual language onto precise themes that open the viewer up to contemplation on the nature of reality and the miracle of existence.

Each piece in the newest series interweaves considerations of three major sources — a memory of Paris, the stones collected on the shore of Lake Superior, and a reading of William Wordsworth’s 1804 poem Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.

The poem is a meditation on the soul’s preexistence, and how it loses sight of divinity while roaming around this earthly plane. And yet, the poet hopes by the end, if we could remember that sacred fire burning inside of everything, we might finally find the fellowship we are all ultimately after. To see this would be to return to the true communion that we all came from before birth and will return to after death.

Those profound themes were with Koop as she stayed in a cabin on the northern shore of Lake Superior. There, she wandered by the water’s edge, the stones there catching her eye. The beach’s assortment were rocky and divoted — seemingly unweathered. And their colors glimmered with all kinds of textures and colors. The stones seemed to convey the same celestial origins and profound individuality of the souls in Wordsworth’s poem. Here, she’d found the protagonists for a new body of work, one that would contextualize these unique beings in terms of our own relationship to the transcendent.

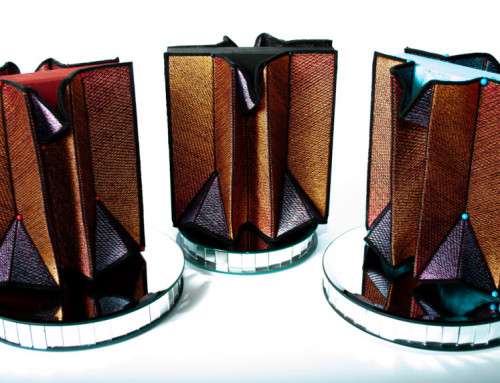

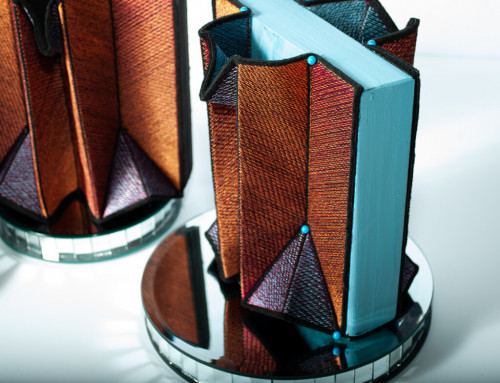

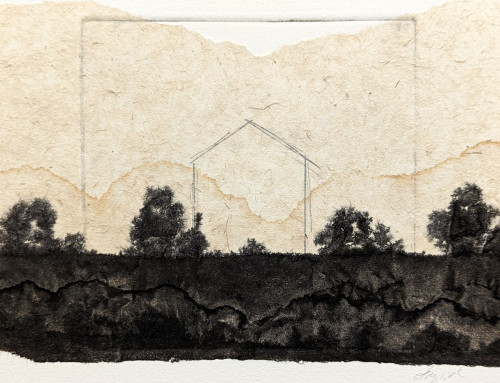

The resulting series features stones nestled into the surfaces of wood panels. On these surfaces, she combines mixed media to heighten the already existing details in the surface — emphasizing, contradicting, or resonating with the embedded stones. In doing this, she manages to create a still greater unity among the pieces through process. It is that greater unity, after all, that is the landing place of the ode.

That greater unity is also the core nestled into a memory from Paris, almost 50 years past. While studying in France, Koop found herself waiting on the platform at the Metro. Her eyes wandered, alighting on a woman sitting on a train. Koop could see such weary sadness in the woman’s eyes, even through the distance and the glass between them. The moment the train began to move, the woman’s eyes rose and met Koop’s. The two women smiled and waved at one another in the brief moment they had before disappearing from each other’s lives. They would never see each other again, but they’d shared something profound, even if brief. True communion.

The works in this series help render palpable experiences like this one, moments where we can see past the mundane pall cast over reality and into the essence of things. This is fitting thematic terrain for an artist whose most enduring influence is Medieval religious art. Those gilded manuscripts, altarpieces, and relics that survive remind us of an entirely different worldview — one where the transcendent was placed above all else.

These pieces are not unlike a reliquary for the stone that serves as their anchor and central subject. Though this idea is persistent throughout, Koop does a wide range of experimentation within these lines.

In XXVI, the dramatic play between blue and orange provides a dazzling background, one that seems not so much to emphasize the stone but appears to be set off by it. The artist takes from the colors already present in the stone and then amplifies them, finding ways to match the abstract visual motifs in the stone by exploring the features of the wood panel with paint. Here, the work of art doesn’t support the stone but erupts out of it. Continuing with the central metaphor of the series, it is as if this soul was sent to the material plane to generate something, and it has no doubt succeeded.

Other pieces offer a much closer marriage between the wood’s surface and the stone’s, presenting a balanced consideration of both. Take XXX, where a waterfall-like pattern passes from the wood, through the stone, and back into the wood’s surface. In this way, the tension between soul and body is relaxed, allowing us to see the possibility for their intimate harmony.

At other times, there is a much more aesthetic force in the piece, and the viewer can begin to glimpse how echoes of modernist composition can be combined with the Medieval impulse to hold up the stone as a relic. Consider III, where the black body of the stone contrasts with the pale colors painted onto the wood’s surface. Placing the stone low gives the piece a bit of visual drama needed to catch our attention, but then we are asked to contemplate more fully the object. If we do, we begin to see this piece of rock as an exaltation of everything holy. While Wordsworth uses his poem to resent the way age gradually robs our ability to see the divine, Koop is here reminding us that if we only looked we could see the divine everywhere. Yes, even a stone is bursting with light.

But Trailing Clouds of Glory Do We Come braids three central ideas — one from the artist’s personal life, one from nature, and one from our shared cultural heritage. At once autobiographical, organic, and ekphrastic, it manages to also serve the higher synthesis of all of these. The series manages this difficult and noble task by drawing on the features Koop has spent her artistic career mastering. The result brings together the simple materials of wood and stone to remind us of that eternal mystical state hidden all around. And when we glimpse it, we may finally know, or remember, true communion.

Jonathan M. Clark, independent critic-